Abstract

This paper aims to highlight the importance of theoretical frameworks of youth work practice that are evidenced based and explores the relationship of the ‘lived experience’ (of both workers and young people) to those frameworks. The lived experience is understood in the context that any social action must begin with the social actors and their own concepts, categories and experience (Fay 2003). It will be argued that without an evidenced based framework of youth work practice workers are destined to use their own ‘lived experience’, and/or the lived experiences of the young people they work with, as the singular guiding principle for practice. Effective youth work practice requires practitioners to maintain the tension between the lived and learnt experience, to makes sense of the experience in the broader context of a theoretical framework that can translate the lived experience into policy, advocacy and change.

Defining and using the lived experience

Manen (1997) notes the importance of the lived experience as a reflective and recollective tool; it is reflection on experience that is already passed or lived through. Andrews and Heerde, (2021), refer to the lived experience as ensuring there is space for those with lived experience to be the authors of their own stories and a narrative for change. Wilhelm Dilthey (1985 in Morris, 2017,) regarded lived experience as having a particular structural nexus and being part of a system of contextually related experiences. These he argued are related to each other like ‘motifs in the andante of a symphony’. Morris (2017) goes on to outline the reading of experience as clearly unique and significant to each person, influenced by both emotive and cognitive processing factors. Past experiences (memories, thoughts and feelings) influence one’s subsequent comprehension of what is occurring in the present. What we know or what we feel about specific events or themes has an influence upon how we understand and process them in the present. According to Barnacle (2004) the lived experience of being in the world becomes a legitimate basis for knowledge.

However, Barnacle goes on to identify that the spectre of ‘non-lived experience’ is a constant companion of research practices that seek to draw principally upon lived experience as its necessary other or counterpoint. An individual’s lived experience is unique and while there may be similarities to the experiences of others it cannot speak for others, to the complexity of others experiences of things such as disadvantage, or vulnerability. Ellis et al, (1992) explored the concept of lived experience within a sociological context. They refer to subjectivity that considers the human lived experience and the political, physical and historical context of that experience. Ochoa and Lorimer, (2017 in Monk et al, eds) suggest that ‘I’ is the narrative that we use as our subjective way of making sense of who we are in the context of our world. They argue that, in a very instinctive way, narratives are pedagogical devices for understanding the world.

Narratives allow us to contextualize events, to make them sequential, causal, and even symbolic. Haven (2007) goes further arguing that from a very young age narratives help us to structure our perceptions of the world. He goes as far as to suggest that stories are the “primary way” in which we interpret reality, reinforcing the lived experience as an individual’s subjective narrative. Vicars, (2021), used Appiah (1994) to assist his understanding of his own narrative whereby the marginalized individual has to narrate another story but, as Vicars identifies,

“I have never found writing easy - never quite sure out of which voice I should speak and none more so than now. As I started to think and write I came to recognise in the telling of myself, a story of negotiating and separation in the ways that I have acted, spoken about and represented myself as a Gay man in education [emerged]” (Piper, & Sikes, 2010 in Vicars, 2021).

As such, this paper draws on Vicars direct experience of negotiating ones lived experience as a narrative that is contextualised to a ‘lived and learned’ model of youth work practice. This lived and learned model of practice keeps a tension between both and will strengthen professional practice by valuing the narratives that inform and create meaning to lived experience and that this lived experience is best understood through a theoretical lens. Narratives of lived experience can inform an empathetic response to others, which is an essential component of youth work. While empathy for another’s lived experience can inform practice it cannot replace important global frameworks such as human rights. Ultimately, it is not collective experience alone that informs youth work practice, but rather the body of knowledge, research and evidence, applied and refined in the context of practice experience, that underpins a professional, qualified practitioner, trained in a theoretical framework of youth work practice.

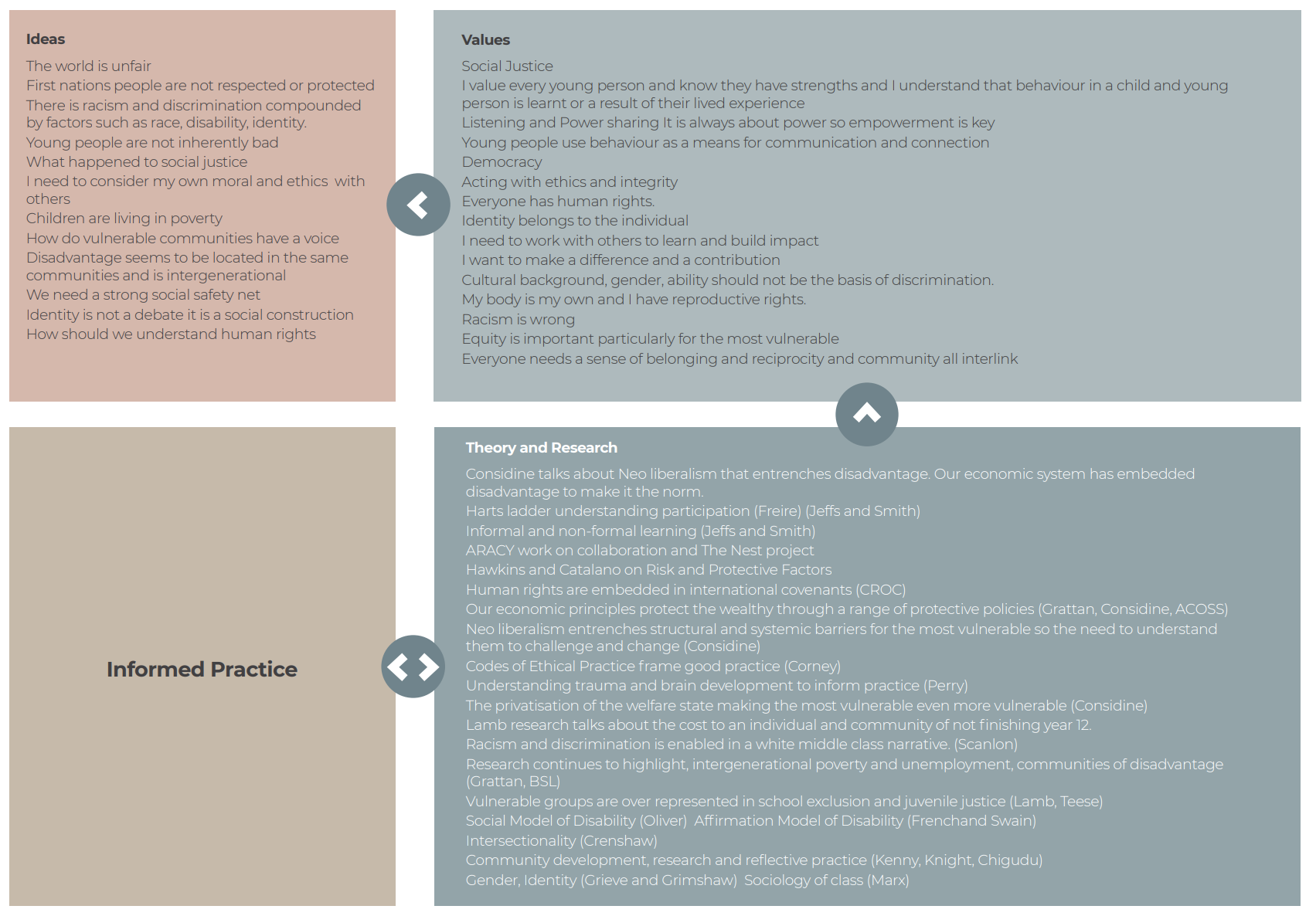

The diagram below outlines how a theoretical framework builds from the nexus of ideas and values to inform practice. Research and evidence make sense of our values and experience building consistent practice that is not formed from one dimension but the rich resources of evidence based research and the knowledge of many.

Theory and Research joins lived experience to inform Practice

The list above is not exhaustive, referring to more seminal work and key pillars of professional youth work. What theory and research, the learned experience, can do is take a value based experience and inform it. Singular lived experience is not a definition for disadvantage it is an example. To build a professional practice tool kit which uses our experience and values we need research and evidence added to strengthen our knowledge and in turn our advocacy. We need to be able to challenge the narrative in a way that understands the inherent faults and barriers that reside within it.

Professional youth work needs to be informed by the experience of others ensuring that their voice is embedded in practice. The advantage of a living and learning model of professional youth work is that practice is informed by both workers experience and by young people’s voices and experience, read through the lens of youth work theory. Respecting the narratives of young people’s experience improves our practice. In turn their narrative is strengthened by theory, that is to say, understanding the political economy and intersectionality of disadvantage and the systemic barriers they face. As a youth work educator I have witnessed a level of empowerment when students understand that disadvantage, intergenerational poverty and the barriers the most vulnerable face is a social construction of conservative neo-liberal governments. This knowledge strengthens youth work advocacy when we understand the neo liberal framework that causes further harm to the most disadvantaged. Australia’s current neo liberal economy places significant structural and systemic barriers in front of many including some of the most vulnerable. It also focusses on the individual as responsible for their own progress/life course limiting intervention from the state.

Sayer in the Monbiot article (2017) in The Guardian on Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations.

It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning. He further argues that the past four decades have been characterised by a transfer of wealth not only from the poor to the rich, but within the ranks of the wealthy: from those who make their money by producing new goods or services to those who make their money by controlling existing assets and harvesting rent, interest or capital gains. Earned income has been supplanted by unearned income.

Vicars, (2021), refers to Brunila and Nehring (2020) to note how ‘affective capitalism means ambivalences, social isolation, heightened anxiety…as well as limited possibilities to speak and to be heard by ensuring that one implicitly learns to find mistakes in, and blame only, oneself. This economic framework is defining a generation as they will be the first generation worse off than their parents (Siminski, 2021). We need to be theoretically informed to challenge these oppressive structures that inform the narratives of all vulnerable young people not just any single example.

As professional youth workers, we need to inform ourselves of all of the evidence on practice frameworks such as risk and protective factors, trauma informed practice, strengths based work, addiction theory and the subsequent neurobiology of different substances. As well as mental health, identity, gender, class and the practice of human rights. These are well researched frameworks that have an evidence base that informs professional youth work practice.

As youth workers, when our learned research, and young peoples lived experience, tells us there is no change for some cohorts - we have a professional responsibility to keep asking questions, advocate for solutions and challenge the dominant narrative about young people. This is particularly the case when it comes to law and order responses and rhetoric often used by government that politicises young people’s experiences without taking any responsibility for it. For example, “Why do we have particular cohorts of young people over represented in the justice system, not just as a recent phenomenon but for decades (Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, 2021)? The neo-liberal narrative would have us believe it is an individual’s fault and responsibility. Why are we not doing more in the out of home care service system given the terrible statistical outcomes for young people who, according to Purtell (2019), are 12 times more likely to enter the juvenile justice system? We must ask questions in a way that can surpass the standard responses we often hear from political leaders.

We need to stay focussed on poverty

The enduring factor that has always pervaded professional youth work is poverty. Much of the current narrative on identity, lived experience and practice has seen this focus more absent from the professional narrative than it should be. The almost impenetrable barrier of poverty, that is too often intergenerational, continues to dominate the life chances and choices of children and young people. According to the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) 1.2 million children and young people live in poverty. That speaks directly to their physical and mental health outcomes, the provision of stable housing, food security, the digital divide, their educational outcomes and their overall life trajectory. This should be at the forefront of our state and national advocacy and be a part of all of our conversations because of the intersectionality of poverty for vulnerable young people. The lived experience of poverty is very real for many of the most vulnerable young people that we may work with. Poverty often accompanies other risks for young people such as family disruption and or violence and abuse, substance use, early school disengagement, unemployment, risk of homelessness and so on. The lived experience of poverty should be high on our list of included youth voice and experience in our practice and should be read through the lens of class, structural inequality and power.

We need to talk more about Power - Empowerment

Young people do not feel they are included in the narrative and those in power remain unwilling to share it. The power narrative about professional youth workers and their practice is important in the context of being an ally, building the voice and capacity of young people and respecting their lived experience as the context in which to work. This should inform and lead all aspects of our work. This also includes understanding power sharing and co-design as central to the practice of youth work.

However, the learned experience can also provide important supplements to the power narrative which is currently old, white and gendered (or what is often colloquially referred to as pale, male and stale) with the sole focus on protecting privilege and wealth. The narrative that is informed by the political economic context is vital to talk about as it locates the power narrative in the broadest context of how to advocate for all young people and in particular the most vulnerable to be included in the decisions that impact on them. A neo-liberal economy deliberately sets out to shrink the welfare safety net excluding many from the resources they require to participate. The wealth divide has grown exponentially in the past two decades leaving many young people behind (ACOSS 2020). We are experiencing the politics of social exclusion. In the recent webinar from the Brotherhood of St Lawrence on shifting the dial on child poverty the panel discussed the importance of child inclusive policies. An excellent example is the very punitive welfare system that many families are trapped in. Parents who have their income impacted for failing one of the many rules that exist within this system has a direct impact on the children and young people in their household. These policies are at the centre of neo-liberal policy power.

As a cautionary note we are currently seeing that power being wielded by a very conservative government in unconscionable ways. The Asylum Seeker Resource Centre refers to three bills that have passed that aim to provide government with a cloak in which to use their power against the most vulnerable. You can see the three bills which they refer to here. At the time of writing this the religious discrimination bill was before the federal parliament and would allow schools and others to discriminate against young people and staff that identify as LGBTQIA. Though perhaps even more concerning is the right of high profile members of the public to use this cloak in the guise of religious freedom to spread what can only be referred to as hate speech. You can read about what is commonly referred to as the Israel Falou clause here.

Our own evidence base and research of practice

Professional youth workers need to research their own practice using a reflective practice model. The absence of which means practice is destined to be limited including our own service and quality of delivery. Understanding the importance of reflective practice as a key component of our professional practice means that professional youth workers start their own cycle of action research which always starts with the young person at the centre and their lived experience and links our learning to build individual capacity and voice, seek out solutions, build advocacy, network to share the learning to build allies, ask questions and be advocates. Our learned experience also ensures that professional youth workers are aware of other research on programs that can provide an evidence base for good practice.

Lived experience and Vicarious Trauma

In the absence of professional training, an evidenced based framework of practice that provides a values and theory lens on practice, workers are at greater risk of vicarious trauma. Hart (2020), in her work on vicarious trauma of youth workers identifies the risk that youth workers face when working with vulnerable young people. Without reflective practice frameworks, workers are at risk of exacerbating their own trauma, the lived experience of vulnerable young people acting as a potential “trigger” for reliving that trauma. In this sense a professional youth worker may use their lived experience to reflect on their practice and inform their learning and in so doing refine their theoretical frameworks of practice. This form of theory and action reflection cycle may enable workers to be more resilient professionals and more empathetic of the concerns and issues faced by vulnerable young people. According to Zuk and Weemore, (in Stamm 1999) in teaching students about trauma it is important to acknowledge in such teaching students do not experience trauma simply as the “other”. They confront and formulate narratives of their own experience. This discussion in no way excludes those with limited lived experience, as we all have lived experience to some degree, it is how we reflect on the interaction of that lived experience in the context of practice that matters. This reflective process strengthens the argument of reflective learning as a theoretical framework that facilitates professional youth work practice that is focussed on the best outcome for every vulnerable young person.

The Pillars of the Learned Experience

The first National Youth Work Consultation 1996 (Broadbent 1997), asked workers from all over Australia …:“please identify critical and discrete areas of training that workers with young people require to work effectively within a changing social, economic and policy environment.” The results hold very similar views to the more recent consultations held by Youth Workers Australia to understand the learning pillars of youth work. Twenty five years ago workers named; understanding the social, economic, and political context, professionalism, values, ethics and codes of conduct, Cross-cultural training, participants identified action research, understanding policy, an ability to measure, evaluate and report on the outcomes of their work and the importance of community development work that underpins all aspects of service delivery for young people. This was parallel to a whole raft of practice skills.

In 2013, seventeen years later Corney and Broadbent undertook a piece of research to inform the (then) Youth Workers Association course endorsement process. They came up with key pillars below that resonate with the earlier work and led to a document that expanded into building blocks for any degree. More recently Youth Workers Australia has undertaken a consultation to inform its Course Accreditation document and once again workers have reiterated many of the same pillars as central to youth work practice. The revised document can be found here.

Here are the pillars that were defined as a result of the 2013 consultation. Pedagogy that is based on a values clarification and reflective practice model that challenges personal values and separates those from the professional values of a Youth Work practitioner.

- An understanding that young people are the primary client/ consideration of the Youth Work practitioner.

- Bibliographies that direct students to required reading that has a focus on important practice values such as: social justice and social action, consciousness raising, empowerment, participation, human rights and advocacy; informal and non-formal education and is reflective of Australian content.

- Ethics education based on relevant state based Youth Sector Code of Ethics/Practice and taught by youth work qualified practitioners. • Content reflective of the social, economic and political structures, influences and barriers young people face.

- Focus on the development of a framework of practice through exposure to a theoretical core of community development, sociology of youth, social structure of adolescent health and youth policy.

- An inclusion of a human rights based social justice pedagogy that includes exposure to diversity, inclusion and inter-sectoral issues such as: age, culture, gender, indigenous sexuality; and ability, within its framework of practice.

- Pedagogy that reflects on the broader social structural systemic influences that impact on young people and youth work practice

These are the constructs of the learnt experience which also provides a pathway for the lived experience as that experience takes its place within the context of formal qualifications and is recognised and credited within the practice frameworks of the course.

Conclusion

The context of the lived experience driving the practice of human service professionals is not new. Certainly in the mental health industry it has been central to practice for some time (Manen, 1997). However, in the youth work sector it has been an ongoing debate with many proponents suggesting that the learned experience is not only unnecessary but detrimental to the lived experience proposing it does not provide adequate weight to the personal narrative. I am confident there are examples of both occurring, in fact, I have seen it and been a part of those discussions. The lived experience can be best understood through a theoretical lens that builds a framework of youth work practice and makes sense of the barriers young people face. The lived experience strengthens our practice as youth workers but the learnt experience ensures all youth workers can be allies and can stand in solidarity. What this paper sets out to do is challenge any one sided narrative to build a more translational foundation to any lived experience of the importance of a theoretical framework of practice. In its absence the discussion turns to a single narrative of whoever is loudest in the room and those we purport to be advocating for, the most vulnerable young people, remain voiceless.

References

ACOSS, UNSW, 2020, Poverty in Australia, ACOSS.

Appiah, K., 1994, Identity, authenticity, survival: Multicultural societies and

social reproduction in A.Gutman (ed) Multiculturalism, Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, pp 161-181.

Andrews, C., & Heerde, J. A., 2021, A role for lived experience leadership in Australian homelessness research. Parity, 34(6), 22–23. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.069383517401855

ARACY, 2014, The Nest Agenda, ARACY, https://www.aracy.org.au/projects/the-nest

Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, 2021, Youth Justice, Australian Institute for Health and Welfare.

Barnacle, R 2004, Reflection on lived experience in educational research, Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 36, no. 1, viewed 2 November 2021, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=edsaed&AN=rmitplus133420&site=eds-live.

Broadbent, R., 1997, National Youth Work Training Project National Consultation Report, Victoria University, Institute for Youth, Community and Education.

Brotherhood of St Lawrence, Shifting the Dial on Childhood Poverty, what will it take? Brotherhood of St Lawrence, https://www.bsl.org.au/news-events/events/shifting-the-dial-on-child-and-family-poverty-what-will-it-take/ (accessed 28 October)

Crenshaw, Kimberlee W., 2017, On Intersectionality: Essential Writings, The New Press

Brunila, K., & Nehring, D., 2020, Affective Capitalism in the Neoliberal Academia. Policy Press.

Coates Brendan and Cowgill Matt, 2021, The JobSeeker rise isn’t enough, Grattan Institute.

Considine, Mark 2001, Enterprising states: The public management of welfare-to-work, Cambridge University Press.

Corney, T. Broadbent, R. 2012, Members Consultation Findings, Youth Workers Association.

Corney, T., 2014, The Human Rights of Young People: A catalyst for the professionalisation of youth work through the development of codes of practice, Chap 1 in Ed Corney, T. Professional Youth Work: An Australian Perspective, Clearing House for Youth Studies, University of Tasmania.

Dean Adam, 2018, Young people involved in child protection and youth justice systems, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Ellis, C., and Flaherty, M., (eds) 1992, Subjective Identity, Sage Publications.

Freire, P., 1970, Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing.

French, S & Swain, J 2000, 'Towards an Affirmation Model of Disability', Disability and Society, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 569-82.

Grieve, N., Grimshw, P., (eds) 1981, Australian women Feminist Perspectives, George Allen and Unwin, Australia.

Hart, K., 2020, Young People Adrift - justice involved young people and their educational needs. Commissioned Report for the Nano Nagle Network.

Haven, K., 2007, Story Proof, Greenwood Publishing Group

Hawkins, J. David, Catalano, Richard Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention, Psychological Bulletin, Vol 112(1), Jul 1992, 64-105.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M.K., 1999, Informal Education: conversation, democracy and learning, London: Education Now.

Kenny, Susan, & Connors, Phil, 2017, Developing communities for the future. South Melbourne, Victoria, Cengage Learning.

Knight, B., Chigudu, H., and Tandon, R., 2002, Reviving Democracy, Citizens at the Heart of Governance, Earthscan Publications Limited, London.

Lamb, S., 2017, Counting the costs of lost opportunity in Australian education, Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

Marx, K., Engels, F., 2002, The Communist Manifesto, Penguin Books.

Monk, N., Lindgren, M., McDonald, S., Pasfield-Neofitou, S., (eds), 2017, Reconstructing Identity: A Transdisciplinary Approach, Palgrave Macmillan.

Morris Gary, 2017, The Lived Experience in Mental Health, Routledge.

Monbiot, George, 2017, Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot (accessed 30th October).

Oliver, M 1996 Defining impairment and disability, in: C. BARNES & G.

MERCER (Eds) Exploring the Divide: illness and disability, Disability Press, Leeds.

Perry, B.D., & Szalavitz, M., 2006, The boy who was raised as a dog and other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook: What traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing, New York, NY: Basic Books.

Purtell, Jade, Muir, Stewart and Carroll Megan, Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care, Australian Institute for Family Studies.

Scanlon Foundation, 2020, Mapping Social Cohesion, Scanlon Foundation.

Siminski, Peter, 2021, 68% of millennials earn more than their parents, but boomers had it better, The Conversation.

Stamm, B., H., (ed) 1999, Secondary Traumatic Stress; Self Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers and Educators, Sidron Press.

Teese, R., 2000, Academic success and social power, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press.

Van Manen, M., 1997, From Meaning to Method, Qualitative Health Research, 7, pp. 345–369.

Vicars, 2021, What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker: An uncanny story of contemporary academic life, in press.

This work has been licensed under the Creative Commons and which is copyright but does enable the reader to freely use any of the material as long as it is attributed to the author.