This article will analyse the systemic and structural factors impacting the precariat and examine the policy and intervention that Guy Standing outlines in his popular works, The Precariat : The New Dangerous Class and A Precariat Charter : From denizens to citizens.

The precariat consists of people that fair badly across seven areas of labour-related security (Standing 2011, p.11). They lack the protections that have been pursued by the organised working class since the Second World War and coupled with a lack of social income, Standing argues that they are alienated from others in the working class (Standing 2011, p.12). They lack a work-based identity built on collective solidarity. The individualism and competitiveness of the globalisation era have been instrumental in the growth of the precariat, in building flexible labour practises and the restructuring of social safety nets into means-testing and "workfare" (Standing 2011, p.26). A central aspect of globalisation is treating everything as a commodity (Standing 2011, p.26). Standing sees a neo-liberal economic model as utilitarianism, with politics a commodity rather than being class-based and value-driven (Standing 2014, p.95-96). There are winners and losers, and the individual must compete.

The regimentation of time that came with industrialisation has made way for encroachment and blurred lines between work and play. The concepts of the working day, week, and what is workplace has been broken down and blurred. Many people are working from their home, their car, or have aspects of their home life occur at their workplace. Those closer to the precariat work harder in fear due to the pressures of labour intensification in such a flexible tertiary society (Standing 2011, p.120). This breakdown makes it harder for workers to secure a job that allows them to plan, whether leisure or career. This unhealthy combination has the precariat under time stress, where occupational skills do not ensure job security, and this opens the doors to opportunism and cynicism (Standing 2011, p.131). Standing claims that with the growth of flexible labour, both neo-liberal and social democratic governments have abandoned traditional models of social solidarity built during the twentieth century. The modern utilitarianism of neo-liberal policy favours the majority over the minority, reflecting in attacks upon diversity as a threat to national identity, against those receiving benefits, the young, the disabled and the elderly (Standing 2014, p.105-118).

Standing states that any movement in the direction of a successful transformation is "defined by the needs, insecurities and aspirations of the emerging class" (Standing 2014, p.113), which used to be the proletariat, but is now the precariat. However, the proletariat was not an emerging class in the twentieth century. It was a well-established class described in depth over a hundred years previous by Marx in Das Kapital (Marx 1887), while Félicité Robert de Lamennais first described the emerging industrial class by this term in 1807 (de Lamennais & Linton 1840, p.9). This is important as understanding the precariat depends on a definition of the proletariat. Standing presents a very limited view of the working class that he defines by industrial stability and security.

It has been claimed that Standings position on the emergence of precarious work is Eurocentric (Scully 2016). The arguments he presents as to the role of those at the forefront of the class struggle are not new, and have been at the core of socialist discussions since the 1800s. For Marx, the educated proletariat would lead the workers to revolutionary action, whilst Bakunin saw that the "most oppressed, poorest, and alienated masses whom he calls the flower of the proletariat" would rise to action and bring triumph to the Social Revolution (Bakunin & Dolgoff 1974, p.287). This position by Bakunin appears to be one that Standing argues for in his work, and much of Standings Charter reflects positions that diverse socialist tendencies have argued and discussed for decades. Standing has redefined the proletariat to an aristocracy of labour.

Standing leads his chapter Politics of Paradise with emotive claims that the first task is to assert that which has been 'denied by labourists and neoliberals' (Standing 2014) and that people should be trusted to act in their best interests. This ignores a whole slew of workers' political positions based on self-management and empowerment of the individual through collective direct action, but more importantly, it divides the working class rather than brings it together. This is particularly confusing when the precariat is so difficult to quantify. It is not other workers that are the enemy of the precariat; indeed, they could soon be part of it. Standings claims that young people are looking to confront insecurities with policies and institutions to redistribute security, while at the same time stating they do not look fondly on 'labourist' employment security (Standing 2014, p.156) does not make sense.

It is not clear by what mechanism Standing proposes to reform neoliberalism into making denizenship fair or recovering identities that he asserts States must allow. The ideals that Standing professes, such as rescuing education and that work must be 'rescued from jobs and labour', seem to have no method, however wonderful it would be if society were structured this way. For example, "Now is the time to assert that pushing everybody into jobs is the answer to the wrong question." (Standing 2014, p.161) is hardly a new position, whether that be in the direct action of the grassroots Australian Unemployed Workers Union, or even amongst the more traditional political parties such as the Australian Labor Party. While comprehensive of much of the positions of the more political left, Standings list of change is nothing new.

The call for a universal basic income is a foundational aspect of Standing's work. However, it is hard to see how this does not fit nicely into a world with fewer jobs and a need for neoliberal control of the working class. This is even more glaring in the light of the argument for universal basic services, and in reading Standing's arguments against it (Standing, 2019), he also falls into the same patterns presented in his previous work of reframing the argument attacking its straw man. The call for universal basic services does not mean accepting the proposals for targeted services (Standing, 2019). Universal basic housing means universal, not targeted or based on a means test. His arguments against free food and that it will be wasted seem at odds with his claims that people should be trusted to act in their best interests. Indeed he claims that 'some people would have an incentive to become food insecure deliberately in order to claim free meals.' (Standing, 2019) which directly confronts his argument that people want to work and will not be disincentivised by a basic income. His arguments not only attack a straw man of less than universal services but also lack consistency and appear to be a shotgun approach to his avoidance of important social safety nets.

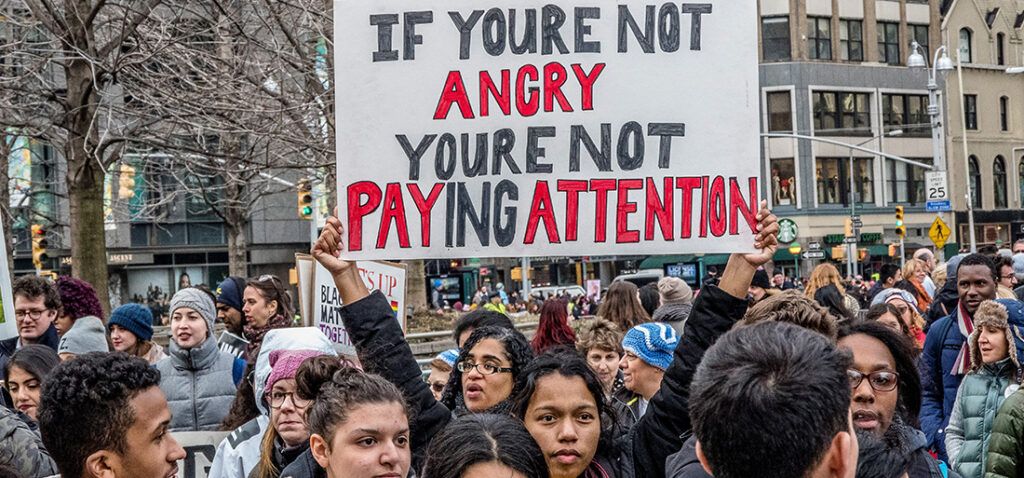

Guy Standing's work in the area of precarity encompasses enormous areas of discussion, and much of that is assertions and lines drawn in the sand between working-class people while at the same time saying we are all susceptible to precarity. A short essay, or two, is not enough to cover this work in any detail. While both his various works can be approached on a line-by-line basis to point out assertions with no evidence and reframing, further research would be better focussed on the arguments that are presented at its core. Standing argues and pushes for a universal basic income, but so are prominent capitalists (Heller 2018). The machinery of capitalism must churn on, and it is hard to see if Standing is not just delaying an eventual collapse by plugging the holes with money. Universal Basic Services, or each according to their ability, to each according to their need can lead to a total breakdown of capitalism and restructuring of the economic system. Furthermore, the examples that Standing puts forward of those working-class people in precarity fighting back call for just that, not policy change, but economic change.

The question that comes from this reading, and the further research that is required, is what model of UBI or UBS, or mixture of both, provides a meaningful way to approach precarity?

de Lamennais, FR & Linton, WJ 1840, Modern Slavery, J. Watson, viewed 23 May 2021

Bakunin, M. A., & Dolgoff, S. (1972). Bakunin on anarchy. New York, A.A. Knopf. viewed 23 May 2021

Standing, G 2011, The Precariat : The New Dangerous Class, 1st edn, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

Standing, G 2019, Why ‘Universal Basic Services’ is no alternative to Basic Income, OpenDemocracy